Reach Revived: A Love Letter to Dub

A tour from Dub's origins, through its position of influence at the end of the Millenium, and onto the artists making some of the most inspired dub-informed music today.

Hey Reachers,

I’ve been taking a little more than a little time off from writing to realign the sights with Reach, and I’m quite excited to get the newsletter running as originally intended. During my break, a fair amount of great new music arrived which could have been fuel for the fire to get started with the publication again, but instead I found myself sidetracked in a reminiscent state, triggered by the promise of summer, going back through my old YouTube dub playlist and invigorating it with some fresh finds.

As nostalgia often does, this phase triggered a reflective moment on how much the genre (and its plethora of offshoots) has impacted me throughout my life, but also about how the genre has influenced more of today’s music than a lot of people seem prepared to acknowledge.

Over the last few years I’ve had more than a few run-ins with people integrated in various music scenes who have nothing good to say for the genre. I’m not going to call out people for not liking a genre of music (as Weatherall said, “music’s not for everyone”) but I feel that if you’re going to hate on something you’d better be prepared to defend your position — at least something more developed than “it all sounds the same”.

A very abridged history: Dub and Reggae bubbled out of Jamaica, and fell into the mainstream (sub)consciousness of the West, not least through the influence of major Western record labels seeking to sign and export Jamaican talent they saw as being on-par (re: record sales) with the likes of Bob Marley.

The genre’s induction into the global Hall of Fame was also due to macro socio-political-economic reasons: in the UK, the ‘Windrush’ movement saw masses of Caribbean black people arrive by boat to “rebuild the country” after the Second World War, and the descendents of those people went on to fashion the music and culture their parents brought into something that represented both their cultural tradition and it’s recontextualisation as children of first generation immigrants living in the territory of their colonisers, people who experienced firsthand the racism of their adopted home. Many Caribbean islanders also made the move to the States, for safety from political turmoil, and for work, and brought their culture with them there too.

The melding of the original skinhead punk and ska / reggae scenes in the UK’s urban areas — largely due to sharing anti-establishment ideology and general societal ostracisation — caused the influence of dub to be palpable in British popular music of the 70’s, 80’s and 90’s. It was integral to the house music boom, as well as the development of early hip hop through sampling; in Return of the Loop Digga, Madlib/Quasimoto leaves a record shop because they don’t stock any reggae, which says a lot about the exemplary digger’s appreciation for the genre.

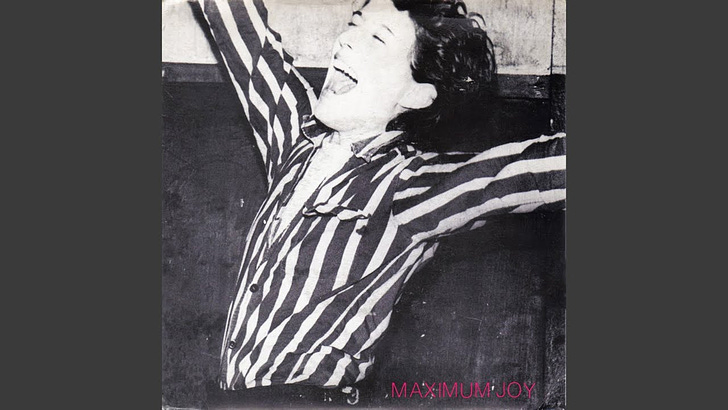

The air-breaking bass of Silent Street / Silent Dub shows how the ever-presence of dub culture bled into the general Bristolian musical consciousness with post-punk outfit Maximum Joy, 1981.

Grace Jones’ 1982 album Living My Life honours her Jamaican heritage throughout, with My Jamaican Guy being probably the most fun joint from the record, while The Apple Stretching carries Reggae’s spoken word narrative traditions.

Paradise Garage legends Larry Levan & Gwen Guthrie released a bumper record of disco cuts for the dancefloor, with Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare, titans of reggae, providing the backing track, 1985.

Sufferer’s Time

One of the main reasons I decided to write this up was to express my surprise that more people aren’t returning to original dub music these days: a music & culture movement began out of ghettoes, and founded on principles of unity and solidarity between the oppressed lower classes of the world, Reggae might have been made famous through The Wailer’s seemingly peaceful music of little birds, but these were largely intended as songs for a genuine revolution on foundations of inter-group respect and a broad definition of love — Marley’s ubiquitous fame often clouds his crucial role as the tenuous peacemaker between the (very literally) warring political factions in the ‘70s, and as thanks for his seeking to unify the politicians to end the razing of slums, the insipid seeding of cocaine into the island, political corruption and the extorting police forces, he was very nearly assassinated.

All this makes for a very pertinent mix which has lost none of its urgency, and which bears strong resemblance to the current political battles over Black, Indigenous and, perhaps especially, Palestinian liberation. You can listen to music released 50 or 60 years ago and hear the same tribulations which we’re suffering from now, and that the average person has suffered for hundreds of years.

Dancehall superstar Horace Andy adds his voice to the chorus of Jamaican voices calling for (or presaging) “Armageddon” — a metaphor-laced phrase referring to the fall of “Babylon” (Western hegemony) — in ‘95.

The eternally excellent archival label Death Is Not The End have seemingly cottoned onto the value that the reverberations of dub’s essential spirit has for today’s world, initiating a sub-label, 333, to reissue out-of-press and impossibly rare and/or expensive music. In fact, it was learning of this new sub-label a few months ago that switched me back onto dub at the onset of winter, with Jasaro People’s Suffering:

“It doesn’t have to come from no techno”

The above quote comes from a record I picked up semi-recently, Androo’s reimagining of a collection of music by The Disciples. It’s an interesting statement that I highlight because it often feels like most people in modern electronic dance music make the association first with the Basic Channel / Rhythm & Sound dubtechno continuum when hearing the word ‘dub’, which I can assume Androo is against, given his conspicuous framing of this quote.

Electronic music as a whole owes a great deal in stylistics to dub: delay, reverb, overdubbing, live-mixing and more, all of which tools creatively sharpened in the sheds of Lee Perry, Scientist, and contemporaries. Beyond the materials of the music itself, the culture of remixing and recording “versions” of other people’s music is something which may have not originated in reggae, but was an absolutely crucial aspect of it. Longer versions of 7” singles, cut for the dancefloors as “Discomixes”, was a trend copied — perhaps invented in tandem? — by house music producers, who’d spin a popular vocal over a bass-and-drum rooted beat for 7 or 10 minutes to excite the crowd.

Despite this, most of current discourse I see surrounding ‘dub’ and its stylistics is directed towards music that is inherently more ‘techno’ than dub: as mentioned, the classic dub producer’s toolkit of heavy delay and reverb are well-utilised by a huge amount of the modern electronic cohort, and I think this is where the association with the work of Moritz Von Oswald & Mark Ernestus leads a great deal of people.

Techno being what it is to the current paradigm of electronic music, many people are very keen to establish and recall the roots and the heritage of that style, but the influences that went into its inception are often pushed to the perimeter of the discussion.

A recent Telecom Electronic Beats post (wielding AI generated art to boot) quotes techno DJ DVS1 saying that the soundsystem should be a priority feature on the lineup, which is of course a given aspect of any decent dub night. There’s potential for another article going into the cultural impact of the soundsystem — and nothing less than a dedicated article would be capable of fully exploring that impact — and its metaphorical applications, how it’s not just a force of sound that has to be experienced to be believed but a mark of a personalised, unique approach, as well as a deviance from mass-produced speakers and comparatively low-quality sound at events.

In some ways the most tangible legacy of dub in modern electronic (dance) music is as an epithet: track titles like Mushroom Temple Dub, Far Away Dub, Shelest Dub, or those with the alternative "Version” adjunctive, are relatively common. In terms of instruments or culture they are largely divorced from the original musical movement from Jamaica, yet they belong to the extended family of the genre, which expands continually with new and fresh interpretations of the original formula.

What characteristics unify these tracks? Are these characteristics present in the original material? It’s largely irrelevant: just as dub found itself splitting cell-like into dubstep, jungle and more, it’s the “extended family” of dub music which is continuing the traditions of the genre with the most exciting results, for those seeking ambitious sounds.

International Outernational Impartial

It’s curious to watch how dub music interacts with people of other cultures, since it is happily traded around the world. Japan has nurtured a booming fanbase for many decades (and in fact played a huge role in its original proliferation: I highly recommend reading this piece), as has a lot of mainland Europe and a great deal of South America as well, by my understanding; the genre is accessible, to my mind, to people of all cultures who approach it with an understanding of the revolutionary mindset of the originators.

The inter-cultural trading of music and ideas is actually fundamental to the genre. In the UK alone there’s myriad linchpin producers, Adrian Sherwood and Dubkasm being just two immediate examples, who are recognised as true originators and crucial voices in both the sound, and the cultural history of dub: Sherwood’s involvement with African Head Charge and Prince Far I (and a whole lot else besides) undoubtedly set dub as a destination for people looking to be inspired by experimental production in the 80’s and 90’s. Meanwhile, Dubkasm veered towards the traditional, producing exclusive tunes for the likes of Jah Shaka, eventually passing the torch to the next generation of Bristol dub heads (Ossia, Gorgon Sound, Sunun and many more).

While there are always telltale signs of problematic cultural appropriation when it comes to musical genres inseparable from a certain racial and cultural standpoint, I’m far more interested in the examples of genuine and authentic sharing between the cultures — not least because the appropriative is often so pitifully weak — and there’s many such stories to go on.

The “outernational dub” category comes seemingly from Jamaicans themselves, given their predilection for inverting Western phraseology, such as “overstand” to replace understand. It’s more than just dub made by an international crew, it’s music made that is ideologically opposed to borders themselves; a quite anarchist sentiment.

Lately, a brace of releases came my way that all fall into the outernational dub catch-all, which are very worthy of your attention. They don’t exactly modernise the genre, but they are modern interpretations that play a delicate game of recontextualisation with skill.

Last April Boomarm Nation revived its label doings, bringing us Khayin from HiriHara. Formerly known as XJ, the producer has collaborated in the past with Algerian experimental producer El Mahdy Jr. Khayin brings back their collaboration, and also the first new material from El Mahdy Jr in many years, and they weave a pattern of dub here that takes influence from traditional (religious) musics from North Africa and the Arabic diaspora, as well as western club tropes and ambient/field recording compositions.

A week after Khayin, Minnesota label dropped a crucial mixpack of killer club vocal bits. Produced by Deskulling, the featuring vocalists are out of Jamaica’s Duppy Gun collective, who’ve been pushing — to put it lightly — the current definition of dancehall & dub for a good while.

All the music here can be called “dub” as much as the electronic music at the end of the above chapter, yet superimposing this music on top of the original source material shows how much the genre has changed. This piece is very much a grime track, but the lineage of grime is inherently linked to the bloodline of dub.

It’d be tough for me to write about ‘outernational’ sound and not talk about SeekersInternational, to whom I owe my first encounter with the term. I’ll skip the lore, since I intend to write about them separately, but the mysterious crew turn their attention to all the strands of dub music in their works, combining original productions with killer remix-sampling, and a library of vocal samples that builds a genuine narrative throughout their releases.

SeekersInternational recently collaborated with conceptual Japanese musician Mars89, inaugurating the latter’s new label, Nocturnal Technology. Mars89 has been twisting up the norm and doing his own thing for as long as he’s been releasing music, with early releases for Bokeh Versions being a good signifier of his early influence of dub.

Lately, however, he’s been looking towards gruff “urban” dance music structures — check this album for Bedouin Records to know what I mean — and the DANGEROUS COMBINATION LP with SeekersInternational is aligned with this: hard steel and petroleum fumes collide with Jamaican MCs toasting the mic and fractal loop science.

Congratulations!

As a reward for making it through to the end, I’ve put together a little listener on Buy Music Club, pooling more artists and music that, to me, fits this “outernational” feel, if not being outright dub.

I hope you enjoyed this loooong and tangential piece. There’s so much for me to talk about within this genre, and I definitely missed out a lot of what I initially wanted to say. Expect some more longer-form writing in the future about those points. From next week I’m going to be back on covering new and cool (?) music, with BMC playlists, reviews and recent singles that caught my sensory apparatus.