Subvert's Plan for the Artist-Owned Internet; Reach Reads #1

October saw Subvert unveiling a new project, outlining a model for community-ownership of online music marketplaces. Its Manifesto is a 140-page read; a perfect fit to reignite longform articles.

This piece is freely available as a taster example of the longform content to be posted on Reach in the coming months. If you’re new here, Reach recently levelled up, and the blog is transitioning to a paid/free model. There’s an opening discount code with 30% off for annual paid subscriptions in the link above, or you can subscribe for free below:

In 2022, Bandcamp shocked its customers by selling to Epic games. A year later, it was been sold again, to Songtradr, which together with the first acquistion expedited a mass panic in the music industry: what happens if Bandcamp is sold and dismantled? What happens if Songtradr introduces ads to the experience — or worse? Ultimately, it has many people thinking; “where will the underground music community go next, if this haven falls?”

It’s a question lacking a suitable response. Newcomer to the market Subvert positions itself as the answer, not just to this problem but to many like it: an “artist-owned internet”, starting with a “community-owned successor” to Bandcamp but with a model aimed at being applicable for beginning ventures such as venue ownership. It aims to provide freedom from corporate insecurity, and total ownership to the members and owners of the coop, its users: underground artists and labels.

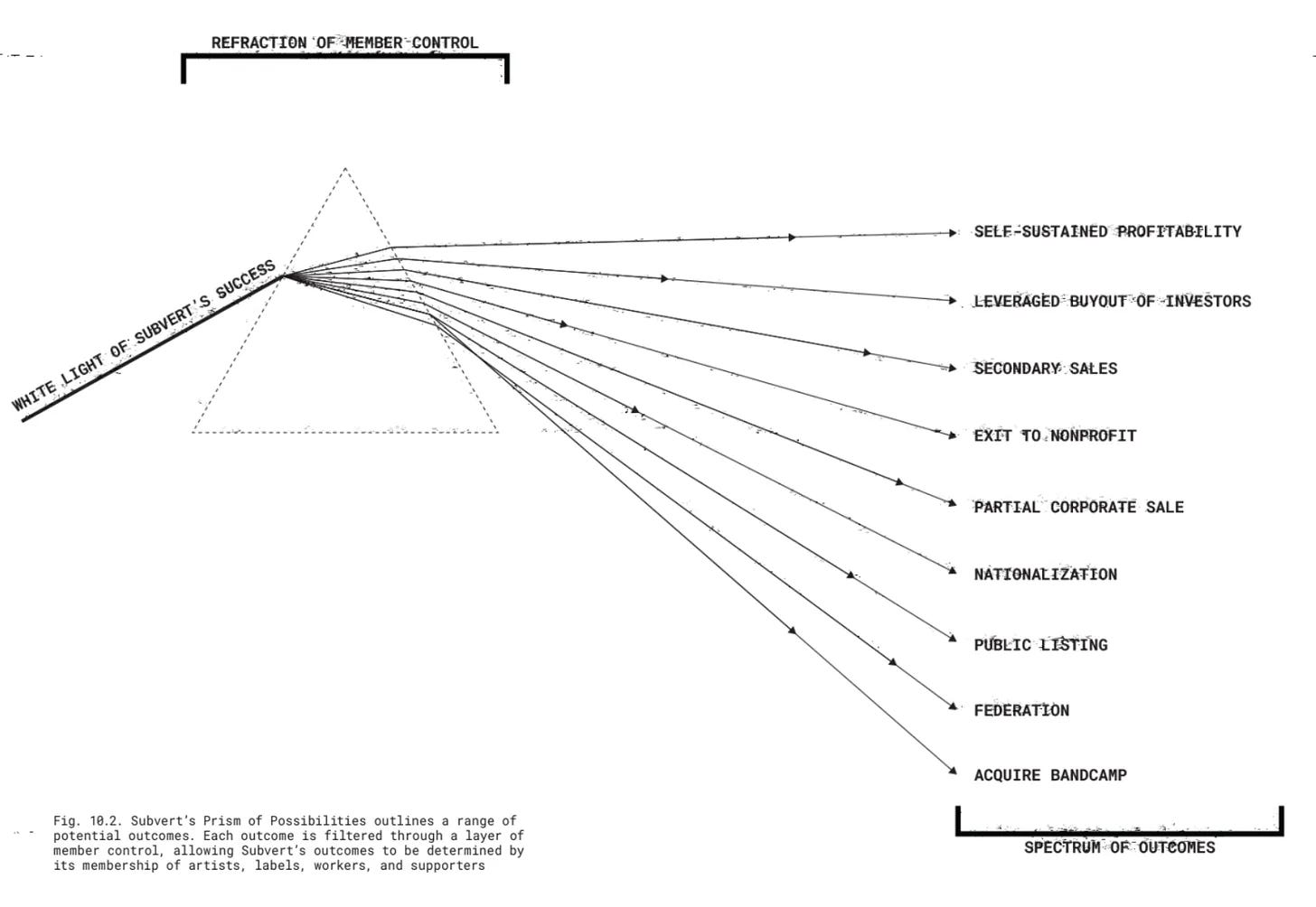

The platform launched its manifesto last month, outlining a business strategy that takes the concept of a social cooperative (coop) and applying it within a corporate (corp) framework, “[leveraging] two legal entities to combine collective ownership with traditional fundraising optionality”; a lot is still in the pipeline, but the idea itself arguably represents a major step forward for collective organisation in underground music.

As such, I’ve been keeping a very close eye on their social media accounts, and I downloaded the manifesto with anticipation on the day of release. It’s taken some time to ready the piece, but below is a summary of what I have understood after dedicating a long time to the manifesto, as well as additional learnings gleaned from an insightful hour-long conversation with the founder, Austin Robey. The article that follows is not a short read, and yet it doesn’t cover the full context, criticism, or an effective description of my entire opinion, which is not exclusively defined as critique. I’ve done my best to focus on providing constructive criticism, but there’s a clutch of reasons why “constructive” is a difficult goal for all of it. Here’s why:

Overview

Subvert’s Manifesto attempts to outline the technical parameters of the proposed business structure while recognising its inability to be precise on certain details, for the present. The main object of information in the Manifesto is the outlining of the physical legal structure of Subvert: the Coop, and the Corp form the two main entities. The Manifesto describes how ownership, and access to it, flows between the two; the members own the Coop, and elect a rotating cast of directorial representatives to manage its activities.

Membership fees are set at $100 for a Supporter, but free for verifiable Artists and Labels (you’ll need a URL to music you’ve released). Supporters will get a digital copy of the Manifesto, which is also available to read on the main landing page. Membership allows access to the Forum, which is presently live, and also to financial reimbursement through the dividends produced by the Platform Shares.

Platform Shares are the main model of distributing the value made on the platform to its Members, the users. By my understanding they operate like standard shares meeting with reward points given for different types of involvement. How users will access these is left largely undefined, but openly so; there’s lots of potential avenues, from uploading music to operating events, and “multipliers” are mentioned, presumably for deeper involvement.

Given the respectably mammoth task in front of Subvert in setting everything up and creating the most tangible online assets, it’s not surprising that they’re limiting the vision in a number of ways, shirking providing a solution to the issues of Streaming to focus on providing a shop for physical merchandise and a digital download store.

In order to achieve takeoff on the stated goals of the Manifesto, the runway ahead of Subvert is fairly short: the financial roadmap looks for 1000 Supporters and $2m of active funds to play with by the end of March. Whatever isn’t achieved with Membership will seemingly be picked up from Investor funding. Investors may also receive “preferred shares”, which I understand to be more typical shares, conferring partial ownership of the Corp.

Analysis

On balance, the Manifesto proposes a number of decent ideas; the framework for the Corp and the Coop is rigid: a Member explained in the Forum that this model was initially adopted by OpenAI; in the same messsage they explain that OpenAI is now backpedalling here due to pressure from its investors. This fact establishes both the power of the model in restricting the involvement of investors, and the ability of their investors to influence and try alter the state of OpenAI’s business model.

Even with my head quite diligently focussed on this piece since the first weekend the manifesto arrived, it still took me several sittings to get through the majority of the text, and there’s bits which I’m still unfamiliar with after spending more than three weeks inside it. It’s not that the Manifesto is wall-to-wall text, rather the opposite; there’s a lot of space, art and diagrams, stylised text and call-out quotes.

The majority of the Manifesto’s word count is given to descriptive or explanatory writing, definitions and so forth. In many places these are essential, but in others the need to define the term feels redundant. Part of the reason why the page count is so high is the amount of words spent covering an aspect of Subvert’s function which is (typically) either self-evident, or basic enough that it doesn’t warrant explaining. The above image displays one typical method of presenting information; a summary header which outlines a point, and then 20-30 words simply repeating the title. Such paragraphs do not crack deeper into the relevance of the idea in a contextualised relationship to Subvert.

The argument made by the platform and it’s author, Austin Robey, is that certain important decisions are to be left unmade until the appointment of the Board, and group-wide membership votes. He’s not wrong to draw a line somewhere, and in some places the vagueries are fine, but in others it is exasperating; while there is arguably sufficient information on the corporate and legal framework to at least have a simple understanding, the remainder of the document is missing very broad and important information about the actual operational agenda of the platform. For example, there’s no discussion of marketing beyond “approaching marketing and user acquisition with relentless persistence and effort”, and using Instagram and TikTok as a medium.

As mentioned, prior to releasing this article’s initial draft I reached out to Austin Robey to discuss some of the ideological and practical points in the Manifesto. I’m glad I did, because some concerns were lessened after the conversation. It’s clear that Robey has his heart in the right place with the project, and that he’s also got the minerals to fundraise for the initial phase, which is unavoidably essential; he explained that Bandcamp received about $5m in investment, in today’s money, to get off the ground. Subvert must do the same, one way or another.

Austin tells me that the document was made as simple as it could be, with regards to the comprehensibility, but also the outline of the document itself. He’s keen to draw the key distinction between Subvert and other business-startups, that the project is to be defined “with, not for”, users, led by their desires and with self-determination baked into the platform’s glue. In the Forum, Robey interacts and discusses with Members the ways in which the Plan could be improved upon and what its limitations might be. It is an encouraging sign to see him engaging in this way, and also being open with the aspects of community organising he’s less technically capable with.

It’s important to relativise that the promise of the title, the “Plan For The Artist Owned Internet”, was seemingly marketed as a battle plan, a solution in stone, but it is largely left unfulfilled when it comes to both a concrete battleplan or a defining ideology to rally behind. Robey explains to me the thinking; the Manifesto is essentially marketing for individuals with the means and skills to help build the platform. It is evident that this stage of the business model needs bodies, minds and bank accounts to hit threshold goals; $100k in Membership signup fees are needed by Christmas. Robey explains that the zine is meeting its goal of being treated like an art object, with artist and labels volunteering to pay for the document, and people buying up the physical copies fairly fast.

This is promising, in some ways; no challenger brand ever succeeded in shifting the needle without generating a bit of hype, and to topple Bandcamp off the top spot will take significant effort, not to mention luck and a fair bit of specific knowledge; Robey’s prior experience with two ventures, Metalabel and Ampled, place him in a good position to secure the private investment needed to get the project off the ground — at least from a financial perspective — as well as other aspects of the business side of things. But there also comes the inverse.

During 2019/20 I was minorly involved with SODAA, a now-deceased community-centred project seeking to create a group of people that would own a clubspace in London. The initial months of the groupwork involved painstakingly assessing the right avenues of approach with regards to divides such as race and class; my experience here led me to expect that Subvert’s Manifesto would give us some direction with these sort of things. Instead, the onus of the work is laid on us, the users and Members, and it’s our job to answer difficult questions: should everyone’s vote really be worth an equal amount? If we collectively decide no, how long would it take to enact the change? These difficult and gritty considerations will prove more difficult to answer the longer the platform is live without formalising binding protectionary measures: it is essential for disempowered groups to have representation, and policy, providing shelter, support and solidarity from the outset of any project which intends to be a part of a collectivist culture, online or otherwise.

Parting Thoughts

There’s a final consideration, which arises as both a fairly comprehensive personal criticism of the entire text on my part, as well as a good explanation for some of the foreshortening of the expected aims of the text; AI has had a significant hand in the generation of the document. I raised this with Austin after our call, and he informed me that the document was authored by him, but with the help of certain AI tools; although the text was then reviewed twice by a human editor, the document’s internal voice, the force with which it asserts itself, is irrevocably reflective of an AI tool.

I can’t say I blame Austin for using the tools to help build the document; it’s far too much work for one man alone. Nonetheless it does raise the very same pertinent questions about authorship and ownership with AI models: how much of this work has been individually crafted, or perhaps just “approved”, is unclear, and I’m loathe to appoint the AI as chief author for fear of offending all those who (very evidently) worked on this, and Subvert as a whole, undermining my genuine support for the platform and its goals. However much was co-written with AI, there is genuine work at every level of the platform’s inception and delivery to this point. The goal is valid.

Subsequently, getting the tone of this document right has been a challenge from the outset, hence the delay, and I really press readers not to rush to conflate this criticism with ill-will. The discussion of these points nonetheless remains essential, especially to me as a writer, and any attempt to mitigate the significance of using AI in this way is utterly unmoored from serious, respectable critical thinking. Discussing use of AI doesn’t have to be equated with lambasting the project entirely, but there are very concrete reasons why AI is not at all appropriate for such a nuanced task.

How can I be sure of my conclusion? My background is in critical linguistics and the English language, and as part of that knowledge set I’m trained to identify certain patterns of keywords, phrases, and argumentational logic. The strongest way the Manifesto can be felt as clearly written by AI is in the passivity of voice: from p.80 and onwards, wording is bloated and overly pragmatic, giving much detail on contextual scene-setting, but any discussion of ‘pitfalls’ or ‘shortcomings’ is two-dimensional, chases its own tail, or provides no meaningful elaboration.

The next thing is to look at what is missing: AI will talk convincingly about everything within the scope of the prompt and resources, but will not be able to discuss details of anything unknown to the model or input, or anything tangible for which it doesn’t know the dataset. This might explain the lack of a well-investigated financial projection chart, with salaries and bills in the plan. AI cannot provide a satisfactory answer here, so it focuses on describing — in aching detail — only the thin outline of a series of considerations.

There is also no attempt at injecting humour, or any aspect of entertaining or creative writing, and not a slight variance in the document’s ability in explaning of any concept. Try doing the same, and you’ll soon find that your mind begs you to vary the way you present information in such a long document. The Manifesto doesn’t bear any defining linguistic traits which are distinct from those of ChatGPT; it doesn’t have a human’s fingerprint.

This portrays a common oversight regarding ChatGPT: it doesn’t do “thinking”. ChatGPT and similar models predict the most appropriate string of words to match criteria within the prompt queue. It pretends like it can think like a human by pretending to write like a human, but it is not appropriate for building a start-up business case or for designing the world’s first online “artist-owned cooperative” as it does not possess critical evaluative skills or a genuine appreciation of context.

This is ultimately the bedrock of all the criticism I’ve given here. If the language of the MAnifesto is pithy and leaves you still hungry for information, it’s because the tool and the author are, for different reasons, unable to provide it. The closing note from Austin declares the importance of the ‘codified safeguards’, but searching for “safeguards” returns anemic results with very little elaboration about what they look like. Robey assured me over the phone that the legal distinctions between the Corp and the Coop are such that Investors and Shareholders will not be able to intercede on the rights or ownership of the Coop at any future stage, and while I personally trust his intentions, that is a position not everyone will naturally take.

I will not be the only one who thought aspects of this Manifesto are written with AI, and though I seem to be the only one willing to discuss it publicly, I do so with the intention of diverting the project away from using such technology in its repertoire; the criticisms here are subject-derivative of AI, and the failings of the tool to provide the information needed in this text is as a result of the tool’s lacking humanity. “The Artist-Owned Internet” might have deserved a more emphatic, human and creative voice than that of an LLM honed into writing good corporate fluff.

For an “artist-owned Bandcamp”, Subvert doesn’t propose any functional betterment to Bandcamp’s model (in tech, site structure, community ideation and so on), besides that of collective ownership, nor does it’s Manifesto contain any language or concepts that I’d hope to see centralised in a radical artist-owned internet. There’s also some very dated ideas: Platform Share distribution decisions will be made by a group of 12 representatives, stratified across each member class, and selected at random — a classic jury, with all its inherent social issues, should not be held as a basis for representation of class, race, gender, etcetera.

The question of the platform’s much-needed workers, which are mentioned frequently as a group of priority and importance within the manifesto, leaves some worry also: I found absolutely no mention of “wages”, “income” or “salary”, only rewards via Platform Shares: how much money do we pay our workers? Who will hire them? How do we decide on who decides? These difficult points are left undiscussed. I’d agree with the counter-argument of the founders that it was never the intention to stipulate so much of the finer details, but these are important considerations to have signalled.

I’m similarly surprised to find a lack of investigation into IRL infrastructure, SEO site architecture, file hosting, serving and management necessities. Market research is also missing: an effective document would discuss competitor market share, but only Bandcamp is discussed here. I can think of more than a few direct competitors in this space, one of which being Nina Protocol, a well-established digital marketplace that achieves everything which Subvert aims to — better, in some respects, as artists retain 100% of earnings and pay no hosting fees — with the sole caveat that Nina uses blockchain “rails” to operate. Subvert’s own stance on the world of crypto is icily critical; discussion of blockchain’s uses are not made or tolerated. Whatever.

You have to navigate to page 62 to find the only mention of Subvert’s hosting fees. The fees are suggested to be put on a pay-what’s-fair sliding scale, but with higher Platform Shares given to those who pay higher fees, once again a phantom hierarchical structure is entrenched within a supposed solution to hierarchy. The high fees of Bandcamp are one of the main reasons why people want an alternative; is this fee model the actual plan, or just an unravelling output? Why was it not included higher up in a more clear position?

Looking Beyond

There remains the inescapable truth that when Bandcamp falls, the successor will need to be immediately available and pre-established. Subvert is right in beginning the work now, which circles the ultimate point: of course Subvert should exist. Its principle tenets of cooperative work are sound, and the unironed wrinkles will likely come out in the wash — or not, but it’s sure worth a try to gain the infrastructure now. Ultimately its unstated point that Nina is not a sufficiently ownable resource does stand. But, I do wonder about the legimitacy of the fears and nervousness about Bandcamp; prior to the two sales of that business, I was never under any illusion that I was paying money to a company just like any other, which seems to be a present fear for those in Subvert’s community, many of whom will make some passing comment that infers their shock at Bandcamp’s recent apparent business activities.

Despite all criticism, the potential for success here is quite quite massive, even if it is only attainable if we can collectively organise ourselves for that success. That’s quite the mission; only a few months ago the community bemoaned the closure of Aslice, which was undeniably a result of failure to spontaneously organise as a group. But it’s new times; a new president comes into power in January, and the States (apparently Subvert’s default market) is abuzz with words about the need to collectively organise for ourselves. Maybe now we’ve had enough of a push to do the work.